Many of greater Basel’s many attractions (An indoor water park and spa! Roman ruins! A push-scooter or sled ride down a small mountainside! IKEA!) are not in the city itself, but in our neighboring Basel-Landschaft, AKA Basel-Land. Basel-Land, which shares our tram and bus lines and was until a battle in 1833 part of the shared canton of Basel, is the much larger canton that wraps around the city of Basel to the South, and represents the entirety of our home canton of Basel-Stadt’s border with the rest of Switzerland (it is surrounded on its other sides by France and Germany).

Basel-Land is interesting in a lot of ways, not least because it’s home to the most amazing public toilet I’ve ever seen, nor because somebody there prints streetwear hoodies that read STRAIGHT OUTTA BASEL-LAND in predictably classic NWA typography, offering some of the world’s least gangster Germanic farm boys the opportunity to demonstrate disproportionate street cred.

Basel-Land also illustrates just how small and rural Switzerland really is. The total national population is under nine million, which means that there are more than 35 cities around the world—seven just in China, and two just in Guangdong province—with more people in them than this whole country. When you take into account that nearly a quarter of the national population is made up of foreigners, things shrink even further: counting Hong Kong, there are a dozen Chinese cities with more residents than Switzerland has citizens. To put this size into a disgusting perspective, several hundred thousand more people voted for Ted Cruz in America’s 2016 Republican primary elections than there are legal Swiss nationals. (Sorry for making you think about Ted Cruz, Americans; if you’re not American and/or don’t know who he is, do yourself a favor and don’t look him up.)

Basel is the third most populous city in Switzerland, and with a population of just over 171,000, it’s slightly smaller than Eugene, Oregon, the 153rd largest city in the United States. I’m originally from Western Massachusetts, which makes Basel slightly larger than Springfield, but slightly smaller than Worcester (in this case, if you’re not from Massachusetts, do yourself another favor and don’t look them up either.)

Assuming you like cities, Basel gives a very pleasantly urban impression thanks largely to its density—although Basel-Stadt is Switzerland’s smallest canton by area, it is also its densest, home to more than five thousand people per square kilometer. One of the first things I noticed and remarked upon when we moved here was that Basel is slightly smaller than the thoroughly charming but undeniably tiny city/moderately large town of Madison, Wisconsin, where I went to graduate school, and which my advisor described optimistically as “almost a city.” But Basel feels more like a real city than Madison, because it’s nearly five times as crowded.

It also punches well above its weight in terms of cultural institutions and attractions, billing itself as the Cultural Capital of Switzerland. Not only does Basel have two charming, minuscule medieval quarters, facing one another across the Rhine and dating from when Grossbasel, the slightly older, larger historical center of the city on the left bank, and Kleinbasel, where we live, on the right, were two separate cities.

(The marriage of the two municipalities seems to have been as contentious as the divorce of Basel-Land from Basel-Stadt; the golden-crowned crowned, clockwork Lällekönig, or “tongue king” figurine has been blowing a mechanical raspberry at the lower classes of Kleinbasel from a perch near the Grossbasel side of the Mittlere Brücke [Middle Bridge] since at least 1658, although the king currently rolling his eyes at us is a 20th-century replica. Giving as good as it gets, when the heraldic mascots of Kleinbasel’s three ancient honorary societies hold a procession through the streets every January, the Wild Maa [Wild Man, also Wildi Maa and Wilde Maa] cruises down the Rhine on a barge accompanied by fifes and drums and cannon fire, swinging a tree branch and keeping his back firmly to Grossbasel.)

We also have a whopping 37 museums in the city or very nearby (some are in Basel-Land, at least one is in the posh suburb of Riehen, one of three towns in Basel-Stadt proper, and about which more below, and one’s in an adjacent town in Germany). We’ve got a Symphony Orchestra, a chamber orchestra, an imposing central Theater in Grossbasel, and an even more imposing Musical Theater in Kleinbasel next to my kids’ school. Over a hundred thousand people check out and buy the work of some 4000 artists every year at the enormous Art Basel art fair, which since its founding here has stretched tentacles into larger hotbeds of wealth and sophistication such as Hong Kong and Miami Beach. A lively, hip, youthful creative culture energized by the more than 12,000 students at the University of Basel, Switzerland’s oldest, permeates Basel’s bars and cafes, club nights, galleries, pop-up boutiques, food halls, and politics (while the country as a whole shows a lot of support for the xenophobic-nationalist Swiss People’s Party, Basel-Stadt’s government is dominated by the Socialists and the Greens).

So Basel looks and feels more urban, and frankly, cooler than Worcester, or Eugene, or dare I say it, Madison, Wisconsin, despite being similar in scale.

But where the city ends, the country starts. Rather than miles of lawns and tract houses in the suburbs, Switzerland offers rolling hills and bucolic villages. In the town of Reinach, just twenty minutes or so from the main Basel train station by tram, you see tractors on the streets, and the skyline of the nearby village of Bad Bubendorf (by skyline, I of course mean a green hillside) is marked by a small billboard for the Swiss Potato Association, a Hollywood sign in miniature reading kartoffel.ch. (Go ahead and check it out—if you can read German, French, or Italian you may find some fine new Rösti recipes.) The aforementioned town of Riehen, wedged between central Basel and Lörrach, Germany, is about ten minutes from the Basel convention center by tram and feels like… what it is, basically, a very pretty little more-or-less country town full of inexplicably rich people.

The denizens of Riehen love Riehen. I peruse a handful of Basel expatriate forums, and whenever a newcomer asks for advice about where they should live, they’re always quick to boost their swanky little town. Residents of most other Basel-area villages are similarly enthusiastic cheerleaders, citing beauty, availability of large houses and gardens, peace and quiet, speed and ease of commuting into central Basel, and, more often than not, safety.

Basel is too loud, gritty, and crowded for a lot of people. And let’s not even talk about Kleinbasel, which is not only the inner city, but the wrong side of the tracks, home to filth, violence, and drunken and/or drug-addled debauchery. When I gave my doctor my address, he raised his eyebrows and stammered, “Oh, ah, that’s not the nicest part of Basel.”

It is true that my block is not very pretty; we live nearly across the street from the convention center, among the city’s largest and least attractive pieces of architecture. And our end of our street is a largely commercial rather than residential strip, built up mostly in minimalist Swiss modern styles, nondescript concrete and glass and steel boxes that sometimes give a rather Soviet impression. It’s also true that our nearest square is popular with people who enjoy drinking cheap beer on the street in the morning (and more about street drinking, which is not against the law here, in another post); a nonprofit organization that serves addicts and the poor has established an Alki-Stübli, or “Alky Tavern,” essentially a dedicated wino zone, including former phone booths repurposed into tiny, socially-distanced indoor lounging areas for use in inclement weather, next to the kiosk there. Basel’s little red light district is also nearby. And on the subject of violence, statistics suggest that Kleinbasel may be the most dangerous neighborhood in Switzerland, with more than a dozen violent crimes per 1,000 residents in 2018: our old stomping grounds of San Francisco had fewer than six times as many.

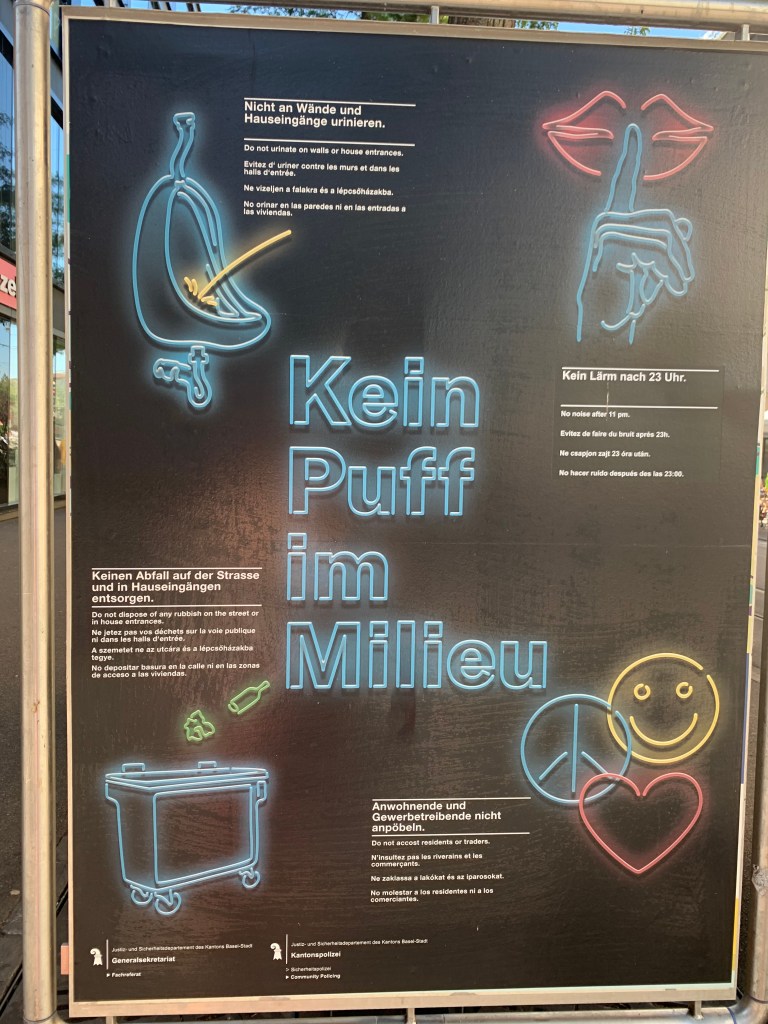

But on the other hand, at the other end of our street is the beautiful, early 20th-century Mittlere Brücke, reconstructed on the site of the first-ever bridge across the glorious Rhine, which was built in the late 13th century. All along the riverside are leafy bike paths and a pedestrian promenade, and dozens of gorgeously preserved medieval houses. (This is about two and a half blocks from my house.) And pretty much every other street in the neighborhood is substantially more historic and attractive than ours. The alcoholics stay home on Sundays, because they have homes to go to. The working girls (who are working legally) are confined to designated, clearly labeled portions of the sidewalk, next to a sign encouraging public order and “No Mess in the Milieu.” And my kids travel freely to and from school, and around the neighborhood, to the store, on the trams, and pretty much wherever they want, all by themselves, because that is what primary schoolers in Switzerland are expected to do. Our neighborhood may be among the most dangerous in the country, but the country is still the safest in Europe, or maybe second safest after Finland.

We have no fear, and we’re very happy in our neighborhood. But we are city people, not villagers.

Parental applause, I know, doesn’t count for much in the offspring’s eyes, but I really enjoyed your wit, writing and eye for detail.

LikeLike